Post by bazooka on Jan 29, 2020 22:18:03 GMT

How Do You Stop a Hypersonic Weapon? DARPA Is Looking for the Answer

DARPA awarded Northrop Grumman $13 million to help develop defenses against a generation of new missiles.

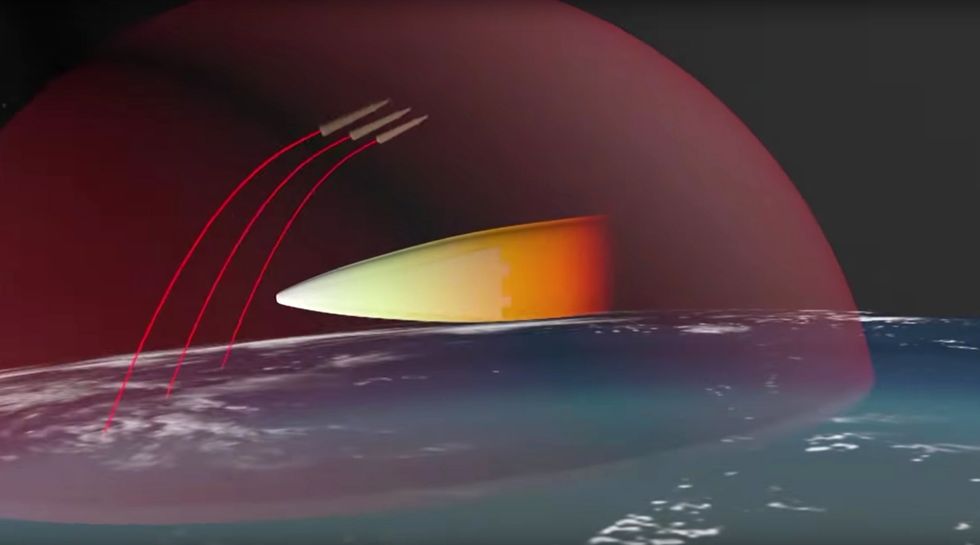

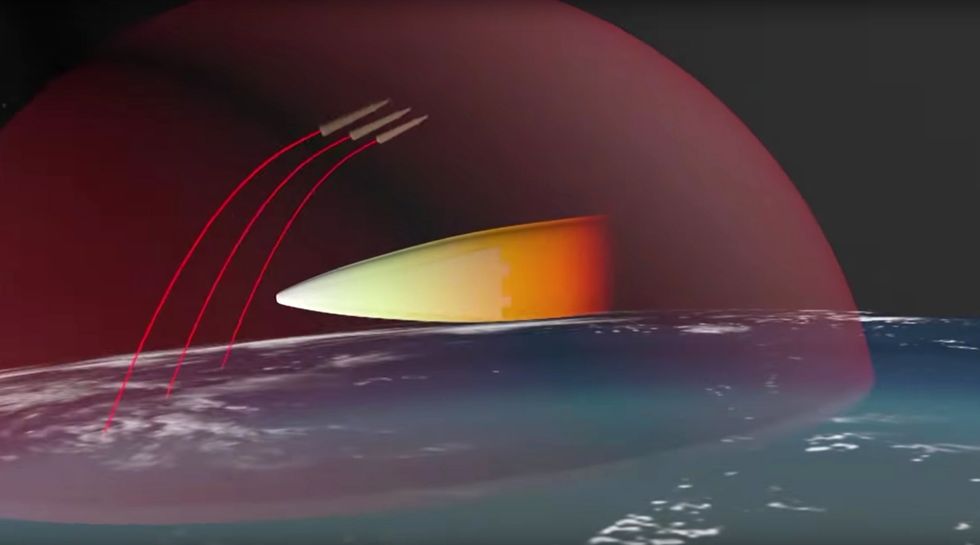

Russian Ministry of Defense graphic showing how hypersonic weapons such as Avangard (right) pass under ballistic missile defenses (left).

TASSGetty Images

DARPA awarded Northrop Grumman $13 million to help develop defenses against a generation of new missiles.

By Kyle Mizokami

DARPA awarded Northrop Grumman $13 million to study defense against hypersonic weapons.

Hypersonic weapons differ from other weapons in traveling at extremely high speeds through the atmosphere, passing under existing ballistic missile defenses.

Russia's new Avangard hypersonic weapon system travels at up to Mach 27, or in excess of 20,000 miles an hour.

The Pentagon’s main research and development agency is pushing to start testing anti-hypersonic weapons this year. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA for short, wants to test systems capable of countering hypersonic weapons as they zip through the atmosphere at more than five times the speed of sound. Glide Breaker could be used against new Russian and Chinese weapons, including Moscow’s new Mach 27 Avangard hypersonic missile.

Hypersonic weapons differ from other weapons in traveling at extremely high speeds through the atmosphere, passing under existing ballistic missile defenses.

Russia's new Avangard hypersonic weapon system travels at up to Mach 27, or in excess of 20,000 miles an hour.

The Pentagon’s main research and development agency is pushing to start testing anti-hypersonic weapons this year. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA for short, wants to test systems capable of countering hypersonic weapons as they zip through the atmosphere at more than five times the speed of sound. Glide Breaker could be used against new Russian and Chinese weapons, including Moscow’s new Mach 27 Avangard hypersonic missile.

According to Defense & Security Monitor, DARPA recently awarded Northrop Grumman $13 million as part of an anti-hypersonic weapon program called Glide Breaker. The contract provides for “research, development and demonstration of a technology that is critical for enabling an advanced interceptor capable of engaging maneuvering hypersonic threats in the upper atmosphere.” The National Interest reports DARPA wants to begin tests of Glide Breaker this year.

One of the most technically ambitious—and potentially dangerous—developments of recent years is the pursuit of hypersonic weapon systems by the world’s major military powers. Hypersonic weapons are designed to move through the atmosphere at speeds greater of Mach 5, or 3,836 miles an hour, or greater. Mach 5 works out to just over one mile a second.

One of the most technically ambitious—and potentially dangerous—developments of recent years is the pursuit of hypersonic weapon systems by the world’s major military powers. Hypersonic weapons are designed to move through the atmosphere at speeds greater of Mach 5, or 3,836 miles an hour, or greater. Mach 5 works out to just over one mile a second.

Russian Ministry of Defense graphic showing how hypersonic weapons such as Avangard (right) pass under ballistic missile defenses (left).

TASSGetty Images

There are a number of ways to accelerate weapons to hypersonic speeds, one method being the boost glide system. Traditional ballistic missiles like the U.S. Air Force’s Minuteman III are large rockets that boost their warhead payloads into low-Earth orbit. After a brief stay in space, the warheads come racing down to the ground, streaking back through the atmosphere to deliver their payloads on target.

Boost glide weapons are similar except they never enter space, spending their entire time in the atmosphere. Boost glide weapons alter course just before reaching space, changing direction to aim their glide vehicle payloads (typically, an arrowhead-shaped vehicle with fins and an explosive warhead) towards a target back on Earth. The glide vehicle then glides back to Earth at hypersonic speeds.

There are a lot of similarities between regular ballistic missiles and boost glide weapons. The main difference—and what makes them desirable to countries such as Russia and China—is that boost glide weapons fly under existing ballistic missile defenses. America’s Ground Based Midcourse Defense system, based in Alaska and California, and the SM-3 interceptor on U.S. Navy ships are optimized to shoot down objects in low-Earth orbit, not in the upper atmosphere.

Glide Breaker is meant to change that. Glide Breaker takes its name from two Cold War programs: Tank Breaker, a program designed to stop Soviet tanks and that resulted in the Javelin anti-tank missile, and Assault Breaker, a similar program that resulted in the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS). Like the previous two, Glide Breaker seeks to solve the urgent tactical problem of its time.

Boost glide weapons are similar except they never enter space, spending their entire time in the atmosphere. Boost glide weapons alter course just before reaching space, changing direction to aim their glide vehicle payloads (typically, an arrowhead-shaped vehicle with fins and an explosive warhead) towards a target back on Earth. The glide vehicle then glides back to Earth at hypersonic speeds.

There are a lot of similarities between regular ballistic missiles and boost glide weapons. The main difference—and what makes them desirable to countries such as Russia and China—is that boost glide weapons fly under existing ballistic missile defenses. America’s Ground Based Midcourse Defense system, based in Alaska and California, and the SM-3 interceptor on U.S. Navy ships are optimized to shoot down objects in low-Earth orbit, not in the upper atmosphere.

Glide Breaker is meant to change that. Glide Breaker takes its name from two Cold War programs: Tank Breaker, a program designed to stop Soviet tanks and that resulted in the Javelin anti-tank missile, and Assault Breaker, a similar program that resulted in the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS). Like the previous two, Glide Breaker seeks to solve the urgent tactical problem of its time.

Flight Test THAAD-23 (FTT-23)

THAAD missile launch.

Missile Defense Agency

THAAD missile launch.

Missile Defense Agency

Intercepting a boost glide weapon system isn’t hard: the weapon will certainly appear on radar and infrared sensors. Hypersonic weapons fly about as fast as incoming ballistic missile warheads, and systems such as the Army’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) and perhaps even the Patriot PAC-3 missile system should theoretically be able to knock them down. The problem is detecting a fast-moving threat that could come from a number of directions, including air, land, and sea. The ability to launch a large number of missiles against the U.S. from an unexpected direction complicates the defender’s ability to shoot them all down.

It’s not clear what Northrop Grumman has in mind for Glide Breaker. The company is working on the Integrated Air and Missile Defense Battle Command System for the Army. IBCS is designed to tie the Army’s radars and anti-air weapons into a single integrated air defense system to defend Army ground units from drones, cruise missiles, and other air-to-ground weapons. If the system could be scaled upward to cover a much larger area it could be the basis for protecting against hypersonic weapons.

Whatever it is, DARPA's $13 million is merely a down payment on what will almost certainly be a very expensive system.

Source: National Interest

It’s not clear what Northrop Grumman has in mind for Glide Breaker. The company is working on the Integrated Air and Missile Defense Battle Command System for the Army. IBCS is designed to tie the Army’s radars and anti-air weapons into a single integrated air defense system to defend Army ground units from drones, cruise missiles, and other air-to-ground weapons. If the system could be scaled upward to cover a much larger area it could be the basis for protecting against hypersonic weapons.

Whatever it is, DARPA's $13 million is merely a down payment on what will almost certainly be a very expensive system.

Source: National Interest